Sustaining our hawker culture, with or without UNESCO

24 Sep 2018

By Neo Rong Wei

GRAPHIC: BELYNDA HOI

GRAPHIC: BELYNDA HOI

In Singapore, our palates are pampered by an array of ethnically diverse cuisines, which can be easily found in our hawker centres. This became apparent to me when Asian food was hard to come by during my semester-long exchange programme in Sweden, almost 10,000 kilometres away from home.

Hawker culture is an important part of our national identity -- it gives us access to food from almost all our local communities. Hawker centres have become a collective space where all Singaporeans can come together to indulge in our favourite past-time, eating.

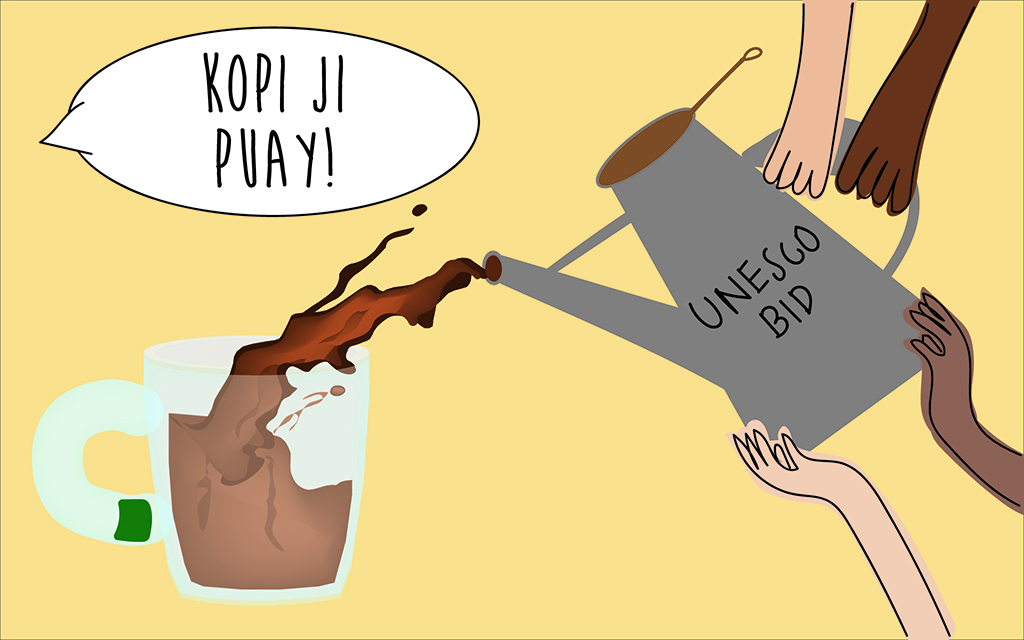

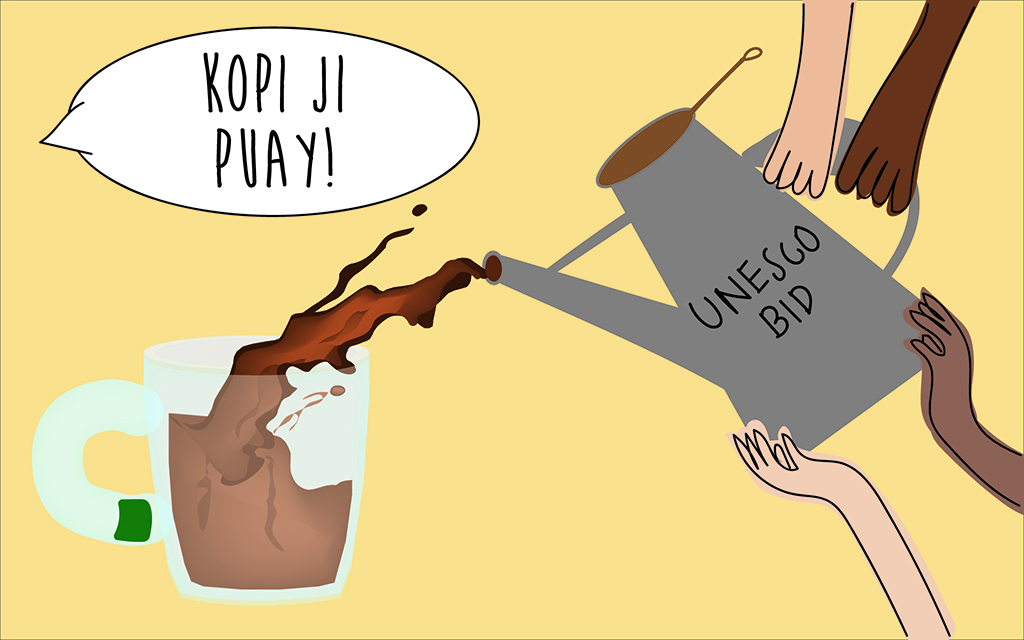

Last month, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced that Singapore will nominate its hawker culture for the UNESCO Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage during his National Day Rally speech.

If the bid succeeds, Singapore’s hawker culture will join the ranks of some 400 cultural elements from more than 100 countries on the list. These include coffee culture in Turkey and yoga in India. The international recognition that follows will promote Singapore’s local food and multicultural heritage, ensuring that this gets passed down to future generations, said PM Lee.

However, this symbolic nomination will save our hawker culture only if we can manage the current problems facing the hawker trade.

Recipe for failure

As the hawker trade’s workforce ages, it risks losing its authentic, traditional hawker recipes as there is a shortage of future talent to pass them to.

The median age of hawkers is about 59 years, which is significantly higher than the national labour force median age of 43 years, according to the Hawker Centre 3.0 Committee Report released in February last year.

Many hawkers like Mr Dai Derong, who has been in the handmade yam and radish cake industry for almost five decades, have retired due poor health. The 82-year-old owned Ah Lo Cooked Food, a stall that used to open to snaking queues almost every day in Chinatown Complex Market and Food Centre, Shin Min Daily News reported.

He called it a day in 2016, without anyone taking over his business.

In response to the hawker trade’s talent shortage, the National Environment Agency (NEA) has introduced schemes, such as the Incubation Stall Programme (ISP), to attract more newcomers to the trade. The programme offers them a stall with basic equipment, at half its market rental fee, for a non-renewable six-month period.

However, schemes like the ISP may be inadequate to encourage a long hawker career. Hawkers have little incentive to remain in the trade beyond the six-month period, as their start-up costs are low and they do not have much to lose. This may result in a high turnover among the new hawkers, making the programme unsustainable.

Old is gold

Another worrying trend is the growing number of non-traditional hawker food stalls.

There has been an increase in the number of hipster hawker centres such as the two-storey Pasir Ris Central Hawker Centre. Its top floor is dedicated to non-traditional fare such as Korean fried chicken and fusion rice bowls, as compared to traditional dishes like

har cheong gai and

nasi biryani on the ground floor.

Customers these days are also more mindful of food presentation. They chase novelty trends, such as salted egg fries and gourmet burgers, in order to post aesthetic food pictures on social media.

“With hipster food, you target the millennials who are not loyal. They will come once or twice, take a nice picture, post it on Instagram and they won’t come back,” said KF Seetoh, founder of food network Makansutra.

Most tourists come to Singapore to taste our iconic hawker dishes like

char kway teow, not gourmet burgers, and these traditional dishes are an integral part of Singapore’s national appeal.

By nominating our hawker culture for UNESCO’s list, I hope that the increased international recognition will inspire more hawkers to be proud of our traditional dishes and preserve them, rather than chase the latest food fads.

Otherwise, even if the bid goes through in 2020, we would not have much of a culture left to protect.

Bring back our traditional fare

To protect our hawker culture, we must first change the mindset of our youth, who are losing sight of the significance of traditional hawker fare due to the ubiquity of air-conditioned and comfortable restaurants and cafes islandwide.

Historically, hawker food originated from the conglomeration of immigrants from other parts of Asia, who brought their food heritage to Singapore. The mix of different cuisines evolved into what we know today as our local fare.

For instance, the

char kway teow we commonly find in Singapore is distinctive to us. It mixes both Teochew flat rice noodles and Hokkien yellow noodles during preparation, due to the strong influences from both dialect groups here.

Such traditional dishes had their origins in the streets, before hawker centres were built in the 1970s to provide a clean environment for these vendors and offer affordable food options to customers. The hawker culture was built by tenacious street vendors who were toiling over their woks and ingredients to make a living.

This heritage should be celebrated and appreciated by Singaporeans. To encourage this, NEA could show more support for the longstanding hawker businesses by offering more grants for the next generation that is taking over. Hawkers should also be allowed to hire non-Singaporeans or Permanent Residents (PR) to alleviate the labour crunch.

More importantly, a collective effort should be made to compile and record the histories of our local cuisine. We should educate the public on how each hawker dish, like

char kway teow, has evolved into something uniquely Singaporean over time, as this would help Singaporeans better appreciate our rich hawker culture.

When, and if, our traditional hawker culture is inducted into the UNESCO list come 2020, what follows should be increased recognition and pride for the trade. Even if the bid fails, we should not take our unique hawker scene for granted, and we must work hard to ensure that it does not become extinct.