Citizen vigilantism may not mean social justice

7 Feb 2019

By Jeanne Mah

Opinion Editor

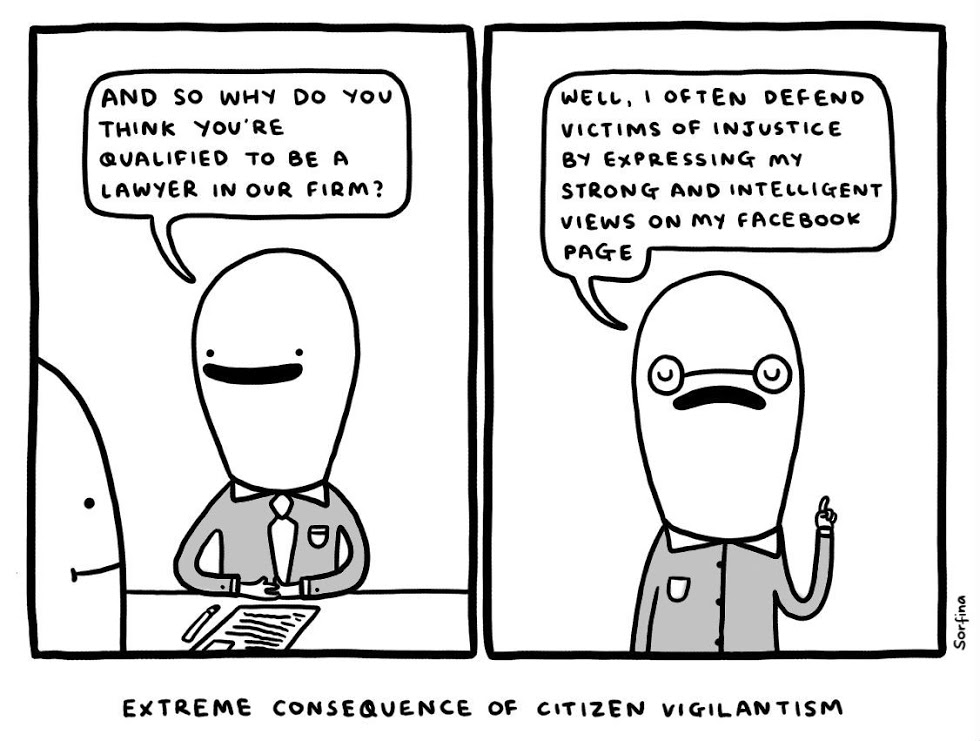

GRAPHIC: NUR SORFINA BINTE IBRAHIM

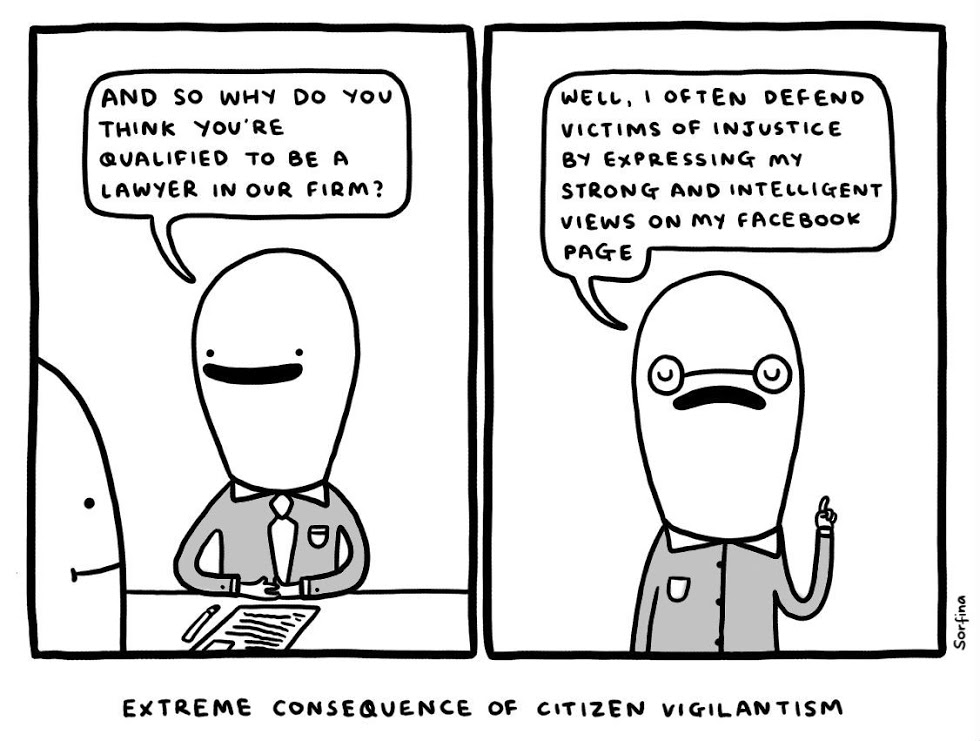

GRAPHIC: NUR SORFINA BINTE IBRAHIM

IN the past three years, our local media has reported on a spate of citizen vigilantism attempts gone wrong. Just last December, a man was wrongly identified as the cyclist who caused a road accident with a lorry in Pasir Ris, causing him to be harassed online. In 2017, netizens also mistakenly identified a couple as the pair who bullied an elderly man at Toa Payoh Hawker Centre and lashed out at them online. The most recent case was the Platinium Dogs Club (PDC) saga in December last year, when vigilantes gathered outside the house of a dog boarder, believed to be neglecting dogs under her care, and obstructing vehicles.

Citizen vigilantes pride themselves on upholding justice when they perceive the government as ineffective in enforcing the law. Once they identify the culprit they believe is responsible for the wrongful act, these citizen vigilantes will try to unearth personal details like the work place of their target. Like an angry mob, they band together to confront the culprit and voice their resentment. This is a problem because they can obstruct investigations by authorities.

In today’s digital era, the proliferation of social media and smartphones has made it easier for citizen vigilantes to operate. A quick search on Google can reveal one’s personal information and social media profiles. In 2018, it was estimated that the number of smartphone users in Singapore reached 4.41 million – almost everyone can easily take videos of incidents they consider unfair and circulate the clips online.

While citizen vigilantism can empower victims and pressure the authorities to take action against wrongdoers, acts of self-perceived justice may worsen the situation at times.

In the PDC saga, the disappearance of a Shetland Sheepdog named Prince, who was left in the care of the boarder, prompted 11 people to gather outside the boarding club to support the dog owner’s search for Prince.

While the group was not violent, police classified it an illegal gathering as a group of people were gathered outside the pet boarding centre. In addition, a 40-year-old man in the group had obstructed a car that was reversing out of the boarding club despite advice from police officers to give way to the vehicle. On 5 Jan, Law Minister K Shanmugam wrote in a Facebook post that it was wrong for people to take the law into their own hands, and assured Singaporeans that “anyone who has engaged in illegal acts will face the consequences.”

Dangers of direct confrontation

Citizen vigilantism on the roads may backfire as well. In 2018, 12 self-incriminating road rage videos were uploaded onto roads.sg, a Facebook page for netizens to submit their in-car camera videos. One of the most-viewed videos showed a driver alighting from his car to hit a taxi with a thick metal rod after the taxi driver had cut into his lane. Netizens were quick to criticise the driver for his rash act and many said he should have remained in his vehicle.

As a driver myself, I have met my fair share of reckless drivers on the road who had put me at risk of an accident. But instead of taking matters into my own hands, I make it a point to send the video clip to the Traffic Police and leave it to the authorities to follow up on the case. I feel that it is not necessary to confront the driver since I have evidence from my in-car camera and it might worsen matters if I argued with the driver.

In a video titled

Are you an angry driver? published by Channel NewsAsia on 16 Jan, Roads.sg director Jason Lim said that in road rage incidents, most drivers tend to feel that they are not at fault, which can rile up a lot of emotions. Drivers should not take it upon themselves to confront the parties involved as this may pose a danger should the confrontation escalate into a fight, he added.

The innocent will suffer

Citizen vigilantism has also caused innocent people to get implicated because of their family members’ wrongdoings.

SMRT Feedback by the Vigilanteh, an online vigilante group that prides itself as “Singapore’s social media badass”, managed to track down and publish photos of Anton Casey in 2014, a Briton who said that Singapore’s public transport was for “poor people” and he wanted to “wash the stench of public transport” off him, and Jover Chew in 2014, who forced a Vietnamese tourist to beg for a refund at his mobile phone shop. Casey was later fired from his job at Crossinvest Asia, and his family had to leave Singapore for Perth amid threats. Chew’s wife was also on the receiving end of prank calls and online harassment, and even had her personal details published on the internet, even though she was innocent.

With over 400,000 likes on their Facebook page, the group has earned the praise of many Singaporeans for calling out people who have bullied others. But the danger in being too eager to call out a suspect arises when innocent people get wrongly accused and shamed online.

In the infamous Pasir Ris incident involving a cyclist and a lorry last year when the cyclist rode in the middle of the lane and later threw a bottle at the lorry, netizens wrongly identified a man named Peter Cheung as the cyclist. He was attacked online, where people criticised his physical appearance and lack of cycling skills. The company he worked at, DDB Group Singapore, subsequently received many negative reviews on its Facebook page. The cyclist was later found to be Eric Cheung, who worked at MCI Group.

In 2017, a video of a couple bullying an old man at a hawker centre at Toa Payoh surfaced online. A man and woman were wrongly identified as the couple by internet vigilantes. As a result, the woman’s company, UOB, also faced a backlash from the public who questioned its hiring practices.

In these instances when innocent individuals become wrongly accused and abused online, citizen vigilantism cannot be tolerated as it causes more harm than good.

Trusting the authorities

Singaporeans should have more confidence in the local authorities to uphold justice and dole out punishment when deemed necessary.

As an owner of a one-year-old beagle, I can empathise with the animal lovers involved in the PDC Saga. However, these people should not have loitered outside the boarder’s home, potentially creating a messier situation involving trespassing or harassment. The legal system exists so that an official sentence can be passed after investigations have been carried out.

This month, it was reported by The Straits Times and Channel NewsAsia that the owner of PDC was arrested by officers from the Agri-Food & Veterinary Authority of Singapore. This shows that our local authorities have been taking the case seriously to apprehend culprits of animal abuse.

In addition, the Singapore Police Force and Traffic Police have warned that they will not hesitate to take action against drivers who commit road rage. Drivers who are physically violent or intimidating toward other road users will be liable to a fine, demerit points, and even a jail sentence. In January last year, a taxi driver was jailed six months for assaulting two brothers in a road rage incident. Similarly, in 2016, a pastor who challenged a businessman to a fight and slammed a van door on him was sentenced to two weeks’ jail and ordered to pay a medical fee compensation to the victim.

Citizen vigilantism can only be justified if the existing system of justice fails to address claims made by victims and punish offenders. Singapore has been consistently ranked in the world’s top five for reliability of police services in the yearly Global Competitiveness Report published by the World Economic Forum. This shows that our police force is proactive in investigating and solving cases.

There are also several avenues for victims to seek legal recourse, such as the Singapore Judiciary which handles minor civil and criminal cases. Those embroiled in conflict with their neighbours can take the matter to the Singapore Mediation Centre, where both parties can talk things through with a mediator. Mediation is a more cost-effective option as compared to going to court. With all these options available, it is not necessary to take the law into our own hands.

However, I do acknowledge that there are instances when citizen vigilantism is effective. According to National University of Singapore media studies instructor Gui Kai Chong in The Straits Times article published in April 2017, netizens who shamed the couple for shoving an elderly man aside and refusing to let him sit at their table at the hawker centre at Toa Payoh had “catalysed enforcement action by the police as it set in motion a wave of moral outage at what happened”.

Furthermore, lawyers said that officers may have made the arrest because of the attention the incident received. The man was eventually fined $1500 for using criminal force by using his body to push against the old man while the woman was fined $1200 for using abusive words with the intent to cause alarm. In this instance, citizen vigilantism may have served as an aid to the justice system – but this seems to be the exception rather than the norm.

As humans, it is only natural for us to harbour anger and feelings of injustice when we witness a wrongful act. However, it is never right to take it upon ourselves to punish others. Citizen vigilantism is not healthy for the society as it encourages mob mentality and may result in the wrongful identification of suspects. We must have faith that our legal system will see that wrongdoers are brought to justice.